There may be nothing bigger than an ‘ant’ between Apple’s Wi-Fi Assist feature and Android’s Wi-Fi Assistant, but the two platforms now demonstrate fundamentally opposing attitudes to freely shared Wi-Fi.

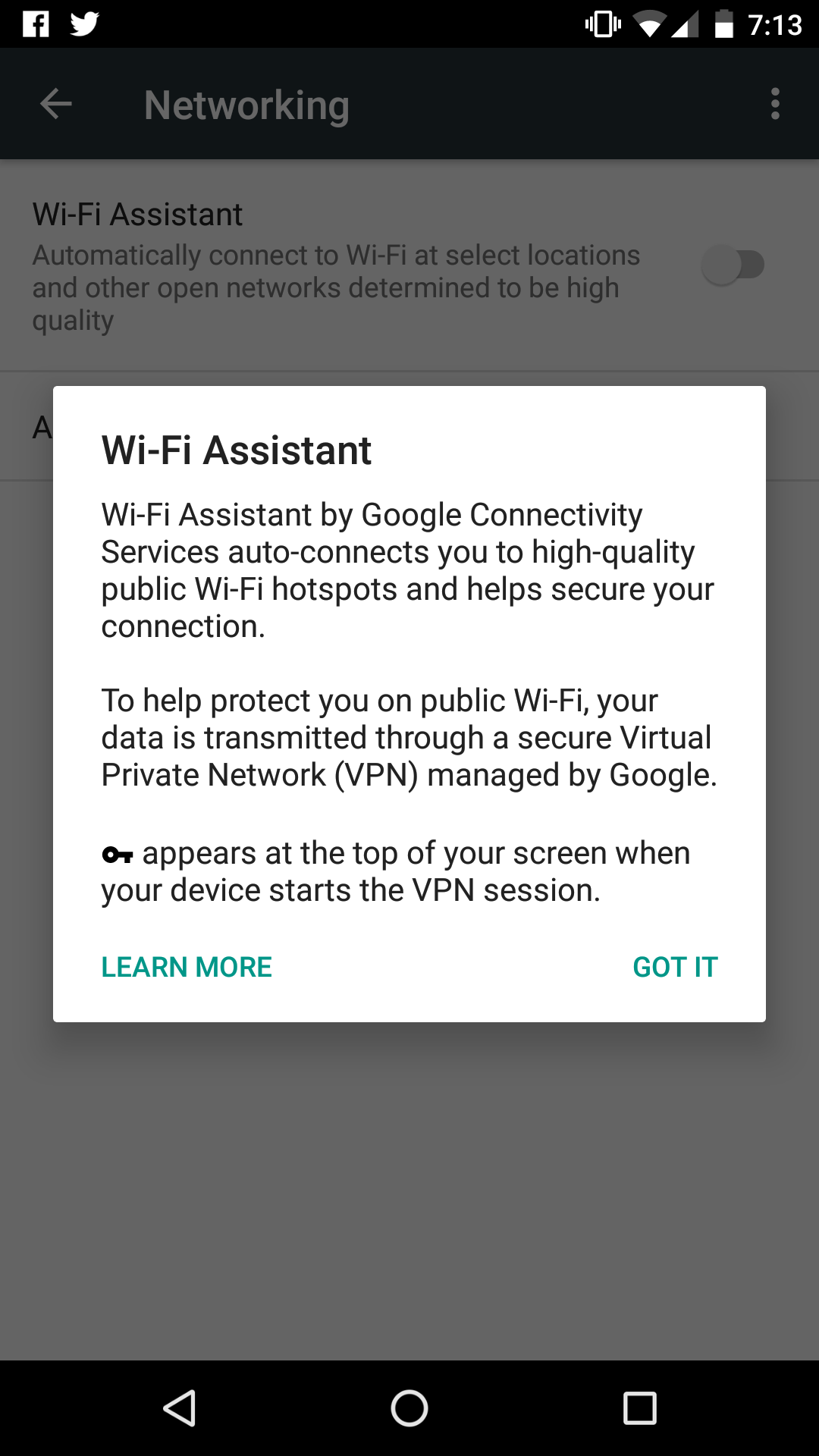

Google recently announced it will be enabling Wi-Fi Assistant (previously exclusive to its Project Fi MVNO customers) on all Nexus devices. Wi-Fi Assistant looks to usher relevant Android devices onto shared public Wi-Fi networks where certain thresholds are met, so the net result will be more Wi-Fi connectivity, in particular over shared, open Wi-Fi in public places.

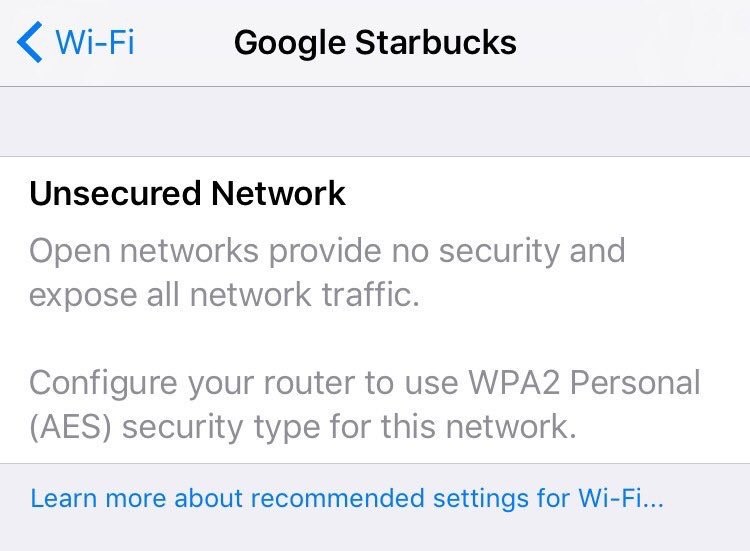

Apple’s Wi-FI Assist, meanwhile, exists to pull devices away from Wi-Fi networks which drop below a certain performance threshold. And with iOS 10 came a new feature which reacts to any open Wi-Fi networks to which the device connects with an ominous “Security Recommendation” flag.

This would appear likely to drive usage of Wi-Fi down — especially public Wi-Fi because, more often than not, home Wi-Fi is now secure by default.

This is nice, clear differentiation.

In addition to connecting to open networks automatically, the Android solution fires up a VPN to secure the traffic, at least within the open network. While there may be some objections around privacy — the VPN termination is at Google — this is a robust way to provide relatively secure access.

But is it really necessary? Certainly as long as the VPN is configured to reject traffic to and from the local network, it protects against local attacks on the device originating from the network. But shared public Wi-Fi networks configured with client isolation (with which devices on the network are permitted to communicate freely with the Internet, but not with one another directly) provide similar protection.

But is it really necessary? Certainly as long as the VPN is configured to reject traffic to and from the local network, it protects against local attacks on the device originating from the network. But shared public Wi-Fi networks configured with client isolation (with which devices on the network are permitted to communicate freely with the Internet, but not with one another directly) provide similar protection.

Moreover, for most users of open Wi-Fi, traffic is typically encrypted end-to-end using SSL connections, so the VPN doesn’t offer a significant improvement in defences. Even searches from mobile devices are usually encrypted now.

There are also downsides. Using a VPN can degrade performance, so some applications might suffer. Others, especially video players which see VPNs as invisibility cloaks allowing users to sneak past geographic licensing restrictions, may not work at all.

With iOS 10, meanwhile, Apple has opted for deterrent rather than protection.

What happens when iOS10 meets a Google Wi-Fi network…

When you tap the info icon alongside the network in your device’s scan list, iOS pops up an information panel which, for me at least, is a little confusing (see screenshot).

An open Wi-Fi network does not really expose all network traffic; any traffic encrypted end-to-end will be protected even over an open Wi-Fi connection. And, while the advice to use WPA2 Personal on a home network is good, there’s not much a customer can do about it in Starbucks.

What these contrasting approaches to Wi-Fi have in common is a desire to be seen acting responsibly in light of any security concerns consumers may have. You can’t throw a stick on the internet today without hitting a scare story about unwittingly surrendering your identity over coffee shop Wi-Fi — thanks largely to the click appeal of any kind of fear-mongering, and much diligent feeding of the press by organizations with security products to sell.

In reality the threat posed by open public Wi-Fi usage is far smaller than some would have us believe.

The risks associated with open Wi-Fi connections arise primarily when traffic is unencrypted between the user’s device and the access point to which they are connected. Anyone in the area with the right know-how can snoop on that traffic. But, as pointed out above, many services we use today are protected by end-to-end encrypted tunnels. So long as the user pays attention to SSL certificate errors (or the apps they use refuse to work unless they can verify they are talking to the right servers), SSL provides far better protection than the Wi-Fi encryption.

In a public setting, encrypting the Wi-Fi network is of limited protection anyhow. It only protects the traffic between the user’s device and the access point; just the first hop in its journey over the internet. Unencrypted traffic would be exposed once more after it leaves the access point. Anyone with access to the router could snoop on the traffic after it hits the wire.

Where multiple people maybe sharing the network, open or encrypted, it is more important to protect against intrusion from other devices on the local network. Client isolation is something that larger shared public Wi-Fi networks usually enable. Smaller venues using consumer grade access points, including all those places with WPA2 encryption turned on, may not have this feature.

All of that aside, the principal reason the risks are far lower than the fear mongers suggest is simply because, relative to the great catalogue of cybercrime options, snooping on Wi-Fi offers very low returns. Large thefts of personal data — the swiping of 500 million sets of customer data, say — invariably stem from hacks into large corporate databases, not people snooping on open Wi-Fi networks, or even snooping on traffic flowing over the internet on the off-chance something useful might float past.

The reality is that the great majority of end users love shared public Wi-Fi for the convenience and cost benefits it delivers. Owners of Devicescape-enabled smartphones typically consume 500MB of data over shared public Wi-Fi every month. Life is an exercise in risk/reward analysis and, where public Wi-Fi is concerned, the rewards are clearly more compelling than the risks.